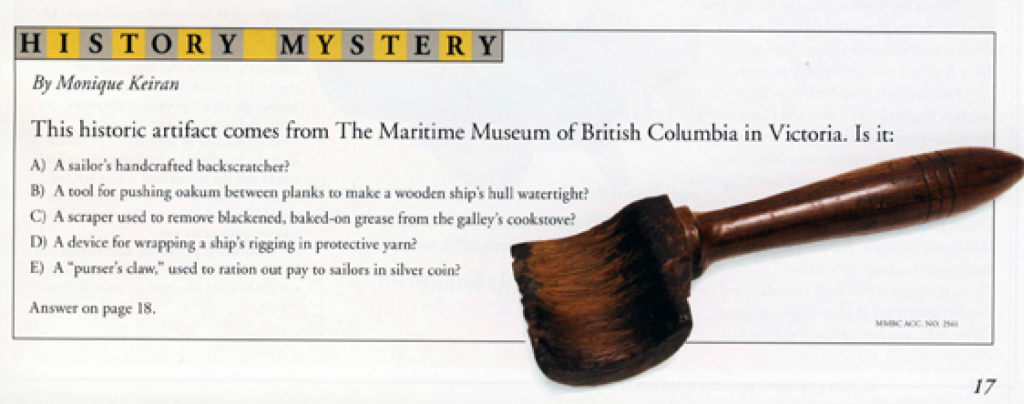

From 2004–2010, I edited the Maritime Museum of B.C.’s member newsletter, Waterlines, and annual journal, Resolution. B.C. Magazine approached me at that time to submit a piece about any strange and unlikely artifact from the museum’s collection for the magazine’s History Mystery quiz column.

Information Forestry, August 2008—Orbiting the Earth more than 700 kilometres above Canada’s forests, a set of satellite-borne sensors collects data from the light reflecting off the planet’s surface.

Beneath the canopy of an eastern Ontario woodland, a Blackburnian Warbler prepares to fly south for the winter.

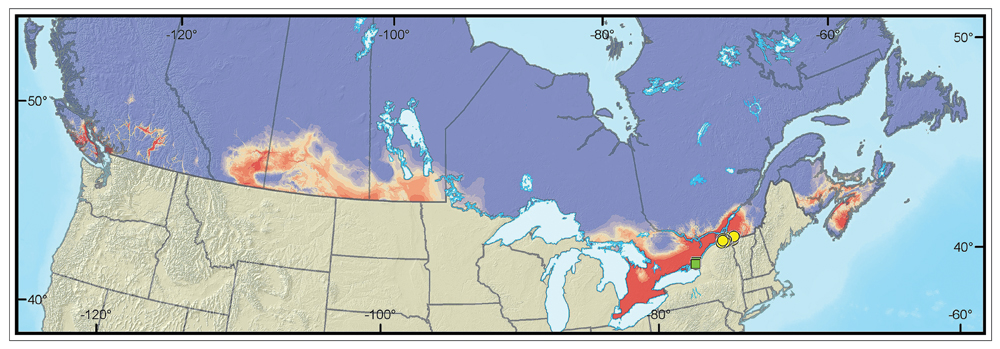

Linking these two phenomena is Biodiversity Monitoring from Space, or BioSpace, a Natural Resources Canada-led project that uses satellite-derived data to track key indicators of biological diversity over time.

BioSpace is the first system of its kind in Canada to use Earth observation data to monitor biodiversity over large areas in a systematic and repeatable manner. Its developers hope it will come to serve as an early warning system to alert governments and resource managers to critical habitat losses and areas with potential species at risk in even the most remote, inaccessible regions of the country.

“Most of the current work used to characterize biodiversity in Canada is very detailed and locally specific, and usually involves someone going out into the field and inventorying specific species,” says project leader Mike Wulder, a research scientist with Natural Resources Canada. “With BioSpace, we’re exploring the big picture: can we use Earth observation data from space to characterize national trends in biodiversity and identify locations where changes in certain conditions may indicate changes in biodiversity?”

BioSpace monitors four key indicators of biodiversity on the landscape, at one-kilometre spatial resolution. Topography drives climate. Land cover indicates types of cover (both vegetated and non-vegetated) and their spatial arrangement. The dynamic habitat index incorporates measures of annual vegetation productivity or greenness, amount of snow cover in winter, and seasonal variation in landscape greenness (an indication of when food is available). The fourth indicator is disturbance of land cover over time.

The BioSpace team recently compared indicator-based predictions of biodiversity to field data collected for birds, such as the Blackburnian Warbler, by the Ontario Breeding Bird Survey and on butterflies in the northeastern U.S.

“Land cover and seasonality are the two remotely sensed indicators that explain most variations in species richness for these two groups,” says Nicholas Coops, University of British Columbia Associate Professor of Forest Resources Management, Canada Research Chair in Remote Sensing, and a member of the BioSpace team. “Birds and butterflies like edge environments: they might live in one habitat, breed in another, and feed in a third. If you’re interested in using BioSpace to monitor the status of bird populations, you would focus on these two indices.”

“It’s very expensive to go out and monitor every single species at risk,” says Natural Resources Canada Biodiversity Science Advisor Brenda McAfee. “We don’t have the resources to do that even in the regions that have roads and easy access, let alone in remote regions of the country that have no roads or transportation infrastructure.” BioSpace, she says, would permit her group to report on biodiversity on an ecosystem or landscape level anywhere in Canada. Agreements requiring reports on biodiversity include the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Montreal Protocol’s Criteria and Indicators of Sustainable Forest Management, the Canadian Biodiversity Strategy, and the National Forest Inventory.

In addition, information generated from BioSpace allows researchers and natural resource managers to prioritize field sampling. “BioSpace is not a substitute for field sampling,” says Wulder. “You have to have boots on the ground in order to actually inventory the species and conditions.” BioSpace may facilitate allocation of scarce resources for detailed field studies and species-at-risk conservation.

BioSpace is supported by the Government Related Initiatives Program (GRIP) of the Canadian Space Agency.

“The development of a Canadian dynamic habitat index using multi-temporal satellite estimates of canopy light absorbance” and “Development of a large area biodiversity monitoring system drive by remote sensing” can be ordered from the Canadian Forest Service online bookstore.

Captions:

From the Cover: ist2_3765025-blackburnian-warbler-with-insect: Fragmented forests and woodlands make for important bird and butterfly habitat, according to a recent comparison of indicator-based predictions of biodiversity to field data. credit: © Paul Tessier, istock 2007

© Natural Resources Canada

Information Forestry, April 2008 — In order to measure a disease’s impact on a tree, you need to know when it became infected. This is difficult to do with root diseases: infection and disease progression occur underground, and above-ground symptoms may not show until years later, if ever. As well, root diseases progress through a stand with time of infections varying between trees.

Natural Resources Canada Root Diseases Research Scientist Mike Cruickshank recently determined how to date infections by root-rot fungus Armillaria ostoyae years after they occur.

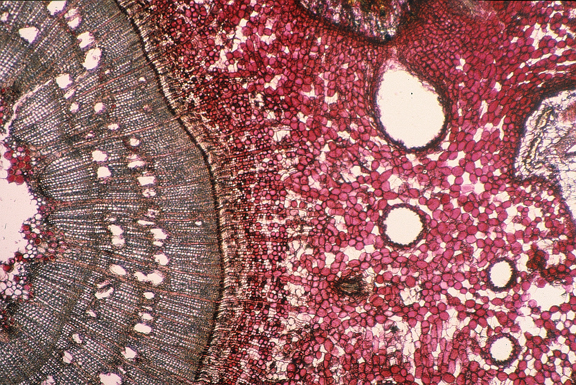

His method traces a defense mechanism that occurs in most trees. When a tree is wounded or stressed, ducts called traumatic resin canals form under the tree’s cambium and around the affected tissue. If enough develop, the canals create a physical barrier between affected and healthy tissues. The barrier helps contain the infection.

Traumatic resin canal barriers form beneath a tree’s cambium layer in response to fungus infection. By tracing the canal positions preserved within tree rings to nearby lesions, researchers can determine when past infection events occurred.

The canals are preserved within the annual rings of root wood, which is how Cruickshank is able to trace them across the rings to specific fungus-caused lesions.

“Traumatic resin canals allow us to create a profile of infection events over time,” he says. If attacked once, a tree may contain an infection with canals, but the fungus may grow around the edges of the resin barrier and attack the roots elsewhere. “Being able to date infection events by year means we can go back and determine impacts of that particular infection—on growth and production in the tree, as well as subsequent effects in the stand.”

Knowing root disease impact would enable forest managers to more accurately predict future timber supply from high-risk stands, as well as to assess broader economic, silviculture, and climate change impacts.

Root diseases exist in most forests, but are especially common in tree plantations, particularly those where stumps of previously harvested trees are left in place before replanting.

Armillaria attacks the roots of all trees and many shrub and herb species native to British Columbia, but causes greatest mortality among Douglas-fir trees planted in the province’s interior. The fungus is prevalent across Canada and the northern hemisphere.

© Natural Resources Canada 2008

Information Forestry, December 2007—Many insects rely on scent to communicate with each other and to find food and hosts. Setting out traps baited with insect and host-tree smells has long been a technique used by plant health officials to detect and track unwanted pests.

But the scents currently used by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), the federal organization responsible for keeping Canada’s forests safe from alien forest pests, fail to entice all insects of potential concern into detection traps. For instance, baited traps have yet to consistently capture emerald ash borer or Asian longhorned beetle, two non-native insect species infesting regions of southern Ontario. Scientists at Natural Resources Canada are helping the CFIA close these gaps by testing new lures and scent combinations.

“Right now, we’re quantifying what species the lures are picking up and what species they’re missing,” says Canadian Forest Service Entomologist Lee Humble, from the Pacific Forestry Centre. “Our goal is to develop more generic lures and extend the repertoire of lures used to trap nonnative insects that may have already become established in Canada.”

Plant-protection officials set out insect traps baited with scents that attract beetle and moth species to detect and monitor the presence of forest pests. Canadian Forest Service researchers are trying to determine the most effective scents and scent combinations to lure non-native wood-boring and bark beetles into traps.

The researchers are testing combinations of scents released by common host trees, in addition to insect pheromones—scents released by insects that prompt behaviours in other members of the same species.

“Pheromones target specific species or groups of species, and are usually much more sensitive than host-tree compounds,” says Atlantic Forestry Centre Research Scientist Jon Sweeney. “A target insect encounters it, and it responds like, ‘hey, there’s one of me out there calling, and it’s saying let’s get together.’”

But pheromones limit the range of insects detected. “By including a pheromone in your trapping system, you increase sensitivity or detection ability for a particular pest, but you also narrow the focus of that lure,” Sweeney says. “It simply won’t work on a broader range of species.”

“There are hundreds or thousands of insects we don’t want entering this country,” says Peter deGroot, a research scientist with Great Lakes Forestry Centre. “You can put species-specific pheromones out, but it becomes very cumbersome to place and maintain hundreds of traps, each with a different pheromone for a different insect. And in many cases, we don’t have the pheromones, and we have to rely on other things to attract the insect into an area and into a trap.”

Lures based on tree scents, which include ethanol and components of turpentine, entice broader ranges of insect species by mimicking stressed or injured trees—the preferred targets of most wood- and bark-boring insects.

“Determining a suite of lures that attracts a broad range of species is a way to lower the risk of infestation by a non-native pest,” says deGroot. “It helps us find and counter insect problems before they blow up so big we can’t eradicate them.”

Humble, Sweeney and deGroot began testing in 2006. They placed lures at sites in Nova Scotia, Vancouver and southern Ontario that are considered high risk for introductions of alien forest insects. Sites include ports, freight depots, and warehouses. The scientists are documenting and analyzing results collected during the last two years, and will be setting out test traps again in 2008.

© Natural Resources Canada 2007

Information Forestry, December 2007—

A century-long ocean-warming trend may explain the rarity of western spruce budworm outbreaks on southern Vancouver Island since the 1930s, according to a study by Canadian Forest Service scientists Alan Thomson and Ross Benton.

Mild winter temperatures, linked to a rise in sea temperature, have de-synchronized budworm–host interactions in the region: budworm larvae now emerge earlier in the year, while timing of bud flush of Douglas-fir, the defoliator’s preferred host, remains unchanged. The trees do not respond to the early warming because their photoperiod requirements are already met by that time.

Scientists compared more than 80 years of sea-surface temperatures from Race Rocks Lighthouse (seen in distance) near the southern tip of Vancouver Island with historic air temperatures.

More than eight decades of sea-surface temperatures, collected at the Race Rocks Lighthouse near the southern tip of Vancouver Island, were compared with corresponding historic Environment Canada air temperatures. Mean sea surface temperatures and the mean maximum and minimum air temperatures from January to March correlated, with all temperatures from this region increasing over the period studied.

The good news does not extend beyond the south island, however: changing climate is believed to be contributing to a widespread, 30-year budworm infestation in the interior, far from the influence of sea-surface temperatures.

© Natural Resources Canada 2007

Information Forestry, December 2007 — Canada’s climate is changing, and forest pests are on the move.

In order to track and predict long-term effects of a warming climate on pests, Natural Resources Canada scientists use a software tool originally developed to help forest managers plan short-term pest control or sampling activities.

This tool, called BioSIM, links insect life-cycle models to weather data and manages their output to determine the timing of specific stages in an insect’s life cycle—for instance, when an insect reaches the stage most vulnerable to pesticide applications. BioSIM has recently been extended to help in forecasting where current or future climates might favour invasion by an alien species because the weather is, or will be, more suitable for its survival.

“The success of forest pest control programs hinges on the vulnerability of pest populations at the moment of intervention,” says Canadian Forest Service scientist Jacques Régnière, who studies insect population dynamics and developed BioSIM. “With insects, weather conditions are a controlling factor.”

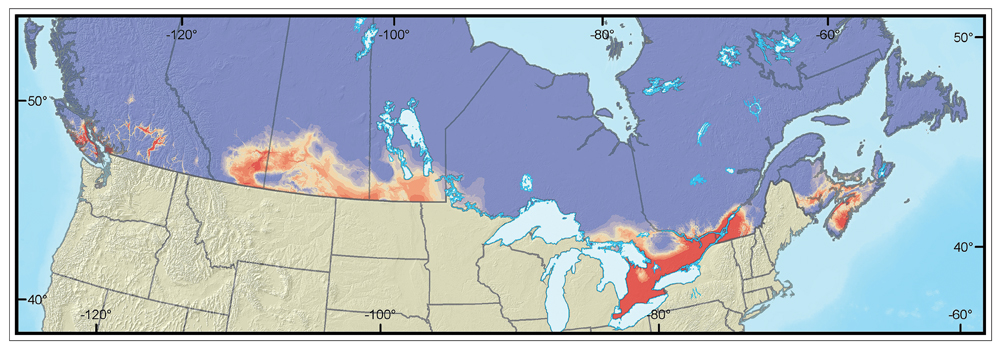

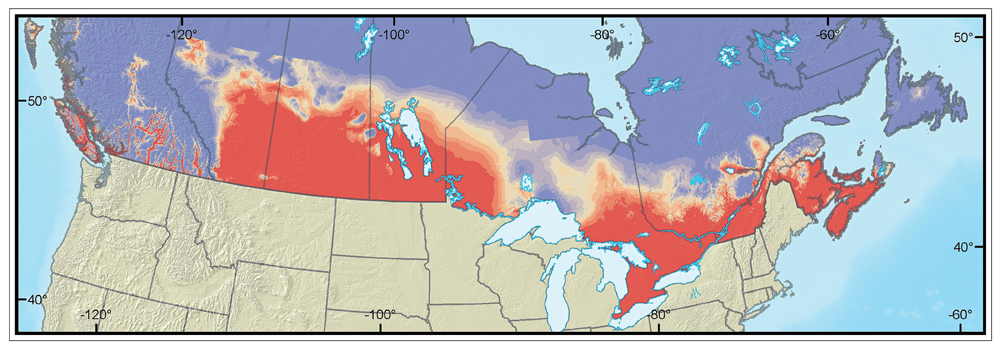

In order to predict long-term climate effects on insect populations, the researchers use data from climate scenarios generated by the Canadian Global Circulation Model that extend many decades into the future.

“Taking BioSIM from immediate applications to seasonality modeling and establishing probability over long time periods was a bit of a leap in complexity, but not much of a change in paradigm,” says Régnière. “Whether you’re looking for short-term or long-term views, it uses the same technology: weather-data management and model-output synthesis.”

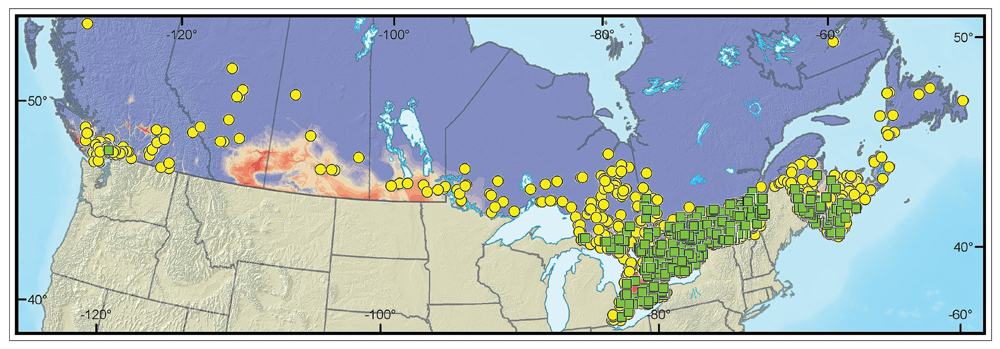

Régnière teamed up with fellow-Canadian Forest Service researchers Vince Nealis and Kevin Porter to determine probable range expansion of gypsy moth in Canada. At the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA)’s request, they analyzed historical records from Natural Resources Canada’s Forest Invasive Alien Species Database, and current and likely future range of gypsy moth in Canada, based on the Gypsy Moth Life Stage model, climate suitability and host distribution. Using the results, the researchers devised recommendations for gypsy moth management strategies, which they then submitted to the CFIA.

“The real benefits of models like BioSIM from a quarantine management point of view,” says CFIA Forestry Specialist Shane Sela, “are that they allow us to better assess risks, and more effectively allocate resources to critical areas where potential risk is highest.”

Régnière also worked with Insect Ecologist Allan Carroll to predict range expansion of mountain pine beetle in western Canada. According to their results, eastward invasion by the beetle will continue if current climate trends persist.

BioSIM is capable of determining probability of future range for any species—insect, pathogen or plant—because it is designed to work with any model that encompasses an organism’s life history and response to climate. This emphasizes the need to quickly acquire such information for any species that represents a significant risk to Canada’s forests.

© Natural Resources Canada 2007

Information Forestry, August 2006 —Budworms are among the most destructive forest insects in North America. During outbreaks, eastern spruce budworm, western spruce budworm, jack pine budworm and their relatives strip foliage from tens of thousands of hectares of susceptible conifers across the continent.

Western spruce budworm is one of several budworm species that eat evergreen needles in Canada's conifer forests.

Now, thanks to indicators identified by Canadian Forest Service scientists, forest managers may be able to use simple chemical analyses to identify areas at particular risk to budworm outbreaks. Insect Ecologist Vince Nealis and Research Scientist Jason Nault plotted changing chemistry within developing Douglas-fir needles against the ability of western spruce budworms to feed successfully on the trees’ buds. From that, they determined that the same molecular compounds that give evergreens their distinctive smell also indicate the potential success of budworms in a given year.

“An important part of the life history of the budworm has to do with how well it is synchronized with the flush of new buds in the spring,” says Nealis. “We wanted to quantify the relationship between emergence of western spruce budworm and development of the insect’s preferred food, Douglas-fir buds.”

Key to the prediction method is a mixture of complex, aromatic hydrocarbon molecules, called terpenes, found in all evergreen needles. The proportions of different terpenes in the mixture within buds change rapidly, but predictably, as buds develop in the spring. The rate of progression from one dominant terpene to another is closely tied to site temperature. In cooler places or during cooler years, the progression—and bud development—occurs more slowly. This can upset the timing of budworm emergence to bud suitability, with consequences to outbreak risk.

According to retired, now-volunteer U.S. Forest Service Research Entomologist Karen Clancy, who studies resistance in Douglas-fir to western spruce budworm, budworm population success depends on that timing. “Phenology of bud break is probably the most important factor driving resistance in individual trees to western spruce budworm damage, and driving budworm population dynamics.”

Western spruce budworm emerges from its winter shelters in early spring and subsists on older Douglas-fir needles and pollen cones until its preferred food—tender, developing buds—comes into season. If larvae emerge too early or if bud development is delayed, greater numbers of budworms die, and that particular forest stand may benefit from a year without an outbreak.

By measuring the terpene profiles of developing buds using gas chromatography, Nealis and Nault found they can pinpoint where and when host trees would be most suitable for budworm outbreak in a given year and where the risk of damage is greatest. Knowing this allows forest managers to better plan and implement pest management options, and better manage forests in their care.

“They appear to have found a good, reliable, relatively easy way to measure the bud break phenology of individual trees and populations of trees,” says Clancy. “Measuring bud break phenology with other methods like going out and collecting samples and visually assessing each of the buds is very time consuming. If you can clip just one branch from a tree and analyze its foliar terpenes, that’s a phenomenal result.”

Although Nealis and Nault identified the correlation between terpene profile and bud suitability for budworm by performing linked biological and chemical assays on western spruce budworm and its host, Douglas-fir, Nealis suspects “the method can be applied to jack pine budworm or eastern spruce budworm or any of the other budworms.”

Scents of suitability

Terpenes, the molecules that give conifers their distinct smell, indicate tree-bud suitability to budworm attack. In linked chemical and biological assays of foliage from test trees at eight sites in British Columbia’s interior, Canadian Forest Service researchers identified terpene profiles that can be used to predict host suitability for the insect, severity of defoliation, and identify tree resistance to budworm damage.

© Natural Resources Canada 2006