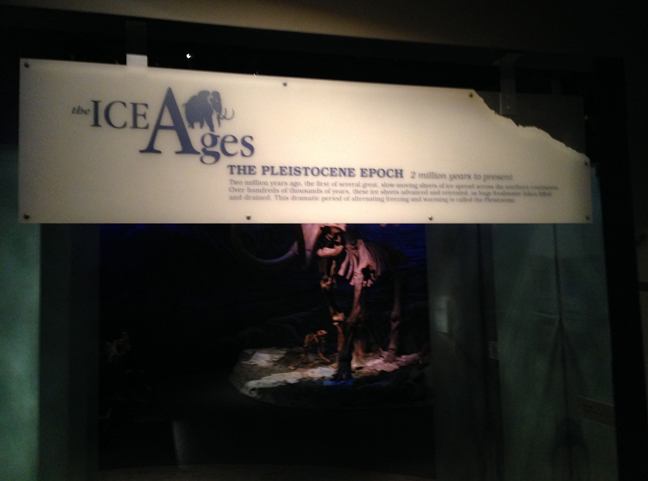

The Pleistocene Epoch

2 million years to present, at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, Drumheller, Alberta

The Royal Tyrrell Museum opened the Ice Ages Gallery in 1999. A collaboration between curators, technical staff, the exhibits team and others, it tells the story of Alberta from two million years ago to the present—the time called the Pleistocene, when huge mammals roamed, great ice sheets came and went, and humans first arrived in North America.

I prepared the text for the panels and labels. Browse through the image gallery below for a view of gallery displays and signage. To read the signage, click on the image.

Glacial ice and meltwater shaped the landscape and affected the climate. A patchwork of grassland, parkland and other habitats developed, known as the Mammoth Steppe. Resembling a cold version of Africa’s savanna, the steppe environment allowed mammoths and other herbivores to flourish.

–Sign text by M. Keiran

Why did the incredible diversity of Pleistocene fauna disappear?

Were Ice Age animals so specialized, they couldn’t adjust to changing environments after the last glaciation?

Did humans wipe out entire populations with their weapons and hunting techniques?

Did animals migrating from Asia outcompete North American species?

Did animals entering North America bring new, deadly diseases?

Or, was it a combination of factors that led to the Great Extinction?

–Text by M. Keiran

Dying out over 20,000 years ago, the giant bison may have been solitary browsers and grazers of open woodlands. Larger than their modern relatives, their horns were more than three times the size of horns on today’s buffalo. The span of the ancient horn cores indicates the extreme length of the horns.

Bison latifrons

Idaho

–Sign text by M. Keiran

With the introduction of new species to North America came a new predator. Humans quickly spread from Asia through North and South America. Using stone and bone tools and weapons, they thrived in these rich hunting grounds and may have caused the extinction of many large Pleistocene animals.

–Text by M. Keiran

You must be logged in to leave a reply.