Someday, our hilltop house may be waterfront property. It won’t happen soon—certainly not this century, and maybe not even this millennium. However, if global warming continues, the surf may indeed break at the bottom of our driveway.

Nature Boy can’t wait.

When I point out the timelines don’t work with his schedule, he says, “Did you ever in a million years think we would live in a house that’s worth what our house is worth now?”

If he’s that excited about sea level rising in the next 200 to 1,000 years, it’s just as well he wasn’t around 11,000 to 13,000 years ago. Bison fossils on the San Juan islands and Vancouver Island suggest lower sea levels at the time created a landbridge from Victoria to the mainland. The link would have allowed plants, bison and other animals to spread here from the mainland at the end of the last ice age.

But the ice age is over, and climate is changing again. Last year marked the 36th year in a row in which global temperatures outpaced the 20th-century average. It was also the 10th warmest year since 1880, when people first started recording temperature.

Continue reading this editorial in Victoria’s Times Colonist newspaper….

Other sources include:

Sea-level rise in 21st Century

Sea-level rise and Vancouver flood protection upgrades

Joint Victoria–Saanich–CRD meeting, November 21, 2012

Victoria Times Colonist, December 1, 2012—Four schools were locked down in November due to cougar sightings, and on Wednesday, CRD’s planning, transportation and protective services committee began considering the new Regional Deer Management Strategy.

Predator. And prey.

No discussion of one can completely ignore the other.

We’ve heard a great deal about the apparent increase in local deer populations, about aggressive deer, increased damage by deer to crops and gardens, and deer-caused car accidents.

Deer have always lived here. They come to our gardens, farms and parks, lured by tasty pickings. They reproduce. They become habituated to humans.

And they are protected by our intolerance of large carnivores, like cougars, wolves and bears, and by our laws restricting hunting, harassment and transport of wildlife.

We create an island paradise for deer. Then we complain.

But, by encouraging abundant deer, we also invite their predators to move in. If we’re uncomfortable with the current numbers of deer, we’re even more nervous about their predators.

In the 12 years I’ve lived here, I’ve seen a cougar once, but I know they’re around. There are too many green spaces, too many new developments squeezing big-cat territory, and too many deer for the region to be cougar-free.

Cougars prefer to eat deer. When deer are unavailable, the cats will prey on rabbits, rodents, raccoons, dogs, house cats, geese… even insects. British Columbians are more likely to be killed by domestic dogs, stinging insects, deer or moose, or other humans than by cougars, but that doesn’t mean we want cougars anywhere near our children or our pets. Or us. Because very occasionally, cougars do attack humans.

Every time a cougar is reported in the area, focus turns on the cats. If conservation officers and their dogs confirm the sighting, the cat is tracked, usually captured and carted away, sometimes killed.

I suspect most cougars that find their way into urban Victoria are young males trying to establish themselves on edges of territories claimed by older, tougher males. They have to be young to be here, because we removed the older cats long ago.

The curious thing is, when we did that, we paved the way not just for the current increase in deer–human encounters, but also for increased cougar–human encounters. According to researchers at Washington State University, when you kill off older, experienced cougars—the cats that have learned to avoid humans—young, dumb cats move in. The youngsters are just looking to survive their first years away from Mom, and aren’t yet wise to the fact that mixing with humans is Trouble.

Every wildlife issue we’ve experienced in the region—the feral rabbits, the abundant and aggressive deer, the less common cougar and bear incursions, the garbage raccoons and the rats—is really a human-management issue. We did away with the predators. We introduced rabbits and rats. We encourage the raccoons and deer. We live in their territory. We don’t learn.

Wildlife biologists agree that coexistence between carnivores and humans depends primarily on managing human attitudes and behaviours. Among the recommendations included in the Regional Deer Management Strategy for decreasing deer–human conflicts are a number that touch on our own unhelpful behaviours.

These recommendations include enforcing municipal bylaws against feeding wildlife, encouraging use of deer-resistant plants in gardens and landscaping, fencing in food gardens and using repellants wherever possible, and generally discouraging deer from habituating to humans.

The strategy also recommends municipalities adjust bylaws to allow higher, deer-proof fences, examine and implement population-reduction measures appropriate to each area, provide support to farmers, in terms of fencing costs, hazing tactics, and crop protection, and adjust signage, speeds, and road-allowance maintenance on roadways to lower the number of vehicle collisions with deer.

It also suggests region-wide public education will be critical.

As capturing and relocating humans from the region aren’t options, addressing our ongoing contributions to wildlife problems is critical.

When we consider the strategy’s recommendations to the CRD over the coming months, we must consider also the broader wildlife implications. Whatever we do about prey species will affect their predators. And vice versa.

And not necessarily the way we intend.

–30–

A version of this article appeared in the Victoria Times Colonist.

Victoria Times Colonist, November 23, 2012—The words “isle” and “isolation” share linguistic roots. Both derive from the Latin word insula, which itself gives us the word “insulate”.

A curious thing can happen to large-ish mammal species that live on isolated, insulated isles. Over long periods of time, some species become smaller.

This phenomenon is called island, or insular, dwarfism. Scientists believe it results from the limited food resources typically available on islands and in other geographically cut-off areas.

In the short term, food deprivation leads to smaller birth weights and decreased growth in mammals. Over the long term, smaller bodies require less energy, or food.

Think of how much a football player or a basketball player or, better yet, a Sumo wrestler eats to maintain muscle mass and energy levels.

When food is persistently scarce, being petite confers a survival advantage.

And, so, over time, mammals on the large side when they live on mainlands may shrink in size when marooned for generations on desert isles.

(Gilligan, the Skipper, too, the millionaire and his wife, and the rest of S.S. Minnow gang weren’t stranded on their island long enough to show the effects….)

Living examples of island dwarfism include the Key Deer, found only on the Florida Keys. The Channel Island fox is the world’s smallest fox. It is native to California’s—you guessed it—Channel Islands.

Here on the B.C. coast, we have the Sitka deer on Haida Gwaii. Columbian black-tailed deer that live on the smaller Gulf Islands tend to be smaller than their mainland cousins. This, despite the abundant shrubberies and other garden delicacies we provide year-round.

Extinct species include dwarf ground sloths in the Caribbean, dwarf elephants in the Mediterranean and small elephant-like creatures in Southeast Asia. The Philippines once were home to small buffalo. Indonesia’s Bali boasted the smallest tiger of all until it went extinct in the last century.

And so, when B.C. Ferries raises rates and cuts service, and adds to the existing physical isolation of B.C.’s islands, the spectre of island dwarfism raises its tiny cranium in my own tiny cranium. As a science nerd, when I hear of the ferry corporation’s proposed cuts to meet budget constraints, I sigh and think of the Hobbit.

Not Bilbo Baggins. Nor the Peter Jackson movie due out mid-December. I’m talking about Homo floriensis, that wee relative of modern humans whose remains were discovered by archaeologists on the Indonesian island of Flores in 2003.

Partial skeletons of nine individuals were uncovered, dating from 95,000 to 13,000 years ago. The tallest would have stood 87 centimetres tall when alive. Hence the nickname, the “Hobbit.”

As ferry service is cut, as it and the options of flying or watertaxi-ing to and from the islands become ever more costly, what with increases in fares, fuel surcharges, airport and dock fees, parking costs, security levies, carbon taxes, cost of living, etc., etc., will our fate as Island residents be to grow ever smaller, as Hobbit Man (and Woman) did on Flores those millennia ago? Will our descendants follow the eventual path to petite-ness taken by the Sitka and local Columbian black-tailed deer? Will we, too, nibble our neighbours’ shrubberies when food imports from the mainland become too expensive? Will decreasing physical contact betwixt mainland and island eventually result in a new hominid species, our very own Homo vancouverislandensis?

Is this the destiny we choose when we choose to continue living here?

Okay, all smart-aleck questions, but the question of choice underlies them.

And it is a choice. Unlike deer, cougar or bear, we choose to live here, despite the cost of living, inconvenience, and limited employment in some fields.

More accessible and affordable alternatives exist… some, where employers are even hiring. Alberta, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, for instance. Where it snows more.

We choose this place.

We must also accept the consequences of that choice.

********************************************************

Note: Nature Boy, wildlife expert, assures me island dwarfism won’t happen in our lifetimes, regardless of the outcome of BC Ferries’ current public consultations or its coming service cuts and fare increases.

“I keep hearing about island dwarfism,” he says, “but I’ve lived here for more than a decade and, well, I just keep getting bigger.”

—30—

A version of this article appeared in the Victoria Times Colonist.

Nov 10, 2012

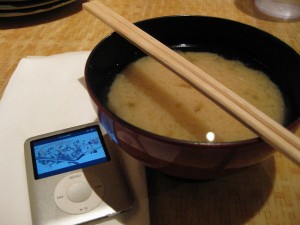

There’s a ritual we go through every time we eat at a Japanese restaurant.

It starts when the miso soup is brought to the table. Nature Boy gives his a swirl with his chopsticks. Then he reverently bows his head over the bowl in silent contemplation.

This is no memorial ceremony for Japan’s recent natural and nuclear disasters. The ritual predates those events.

No misguided adaptation of the Japanese tea ceremony.

Nor is this grace.

No, this prayer-like pause is Nature Boy’s version of veneration for the geologic forces that shape our planet.

So it does, in a way, relate to the earthquake in Japan, and the ties between this coast and that coast. Ties that extend far beyond and deep beneath the more than two dozen Japanese restaurants that operate downtown and the hundreds of students who cross the Pacific every year to study English here. Ties that physically bind this island to those islands in the form of massive crustal plates underlying the ocean floor.

It also relates to the recent earthquake in Haida Gwaii.

For, as I have been informed—repeatedly—in every bowl of miso soup, the same thermodynamic forces that churn Earth’s interior and move continents across the surface of the planet convect clouds of soybean paste and shift shredded wakame and chopped scallions.

In every bowl of soup, a demonstration of plate tectonics.

Those same forces caused the Haida Gwaii trembler, and the recent earthquakes in Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Chile, Alaska, off the coast of Indonesia, around the Pacific Ring of Fire and elsewhere.

The soup itself represents Earth’s mantle, the region of the planet’s liquid interior between solid crust and solid core. The micro-curd miso suspended in the liquid enables The Interested Observer (a.k.a. Nature Boy) to identify convection currents within the soup. Soup at the surface, exposed to restaurant air, cools more rapidly than soup deeper within the bowl. Cool fluid is denser than hot fluid, so it sinks—gravity having its inexorable way. Hot fluid is less dense, so as the cooler liquid sinks, the hot stuff rises to the surface, where it subsequently cools, densifies, and sinks. And so on.

The cycling fluid creates troughs and wells, and pushes the soup’s floaty bits around the surface. Nature Boy gets particularly excited when a piece of seaweed wedges beneath some chopped scallion. He is sure to point out—yet again—the similarities to the Juan de Fuca Plate being driven under the North America Plate in the Cascadia Subduction Zone beneath Vancouver Island.

And I point out the similarities to how my cornea subduct under my eyelids when I roll my eyes.

“That,” he says, “is not at all the same.”

Pause.

“Okay, it is sort of the same.”

But a soup bowl is no crystal ball. No way to foretell a trembler’s timing, location, scale, or scope of impact exists. The October 27 earthquake caught Haida Gwaii residents by surprise. Tsunami alerts followed. Fortunately, despite the earthquake’s 7.7 magnitude, minimal damage occurred and only small ocean waves materialized.

Better to issue a warning when you’re uncertain than to wish you had afterwards.

New technology may provide some predictive potential. The seafloor-sensor network operated by NEPTUNE Canada, the Victoria-based underwater ocean observatory, and the instruments the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute installed this year above the Cascadia fault monitor seafloor deformations. The sensors will provide minute-by-minute information about what is happening beneath our feet and off our shores.

If the data are analyzed quickly, they just might enable some warning of The Big One when it comes. Measurements of the fault zone where Japan’s earthquake happened revealed slow, small slip occurring two days before that quake. Seafloor monitors also detected movement. Unfortunately, the data weren’t analyzed in time to provide notice. Nor could anyone have known slow, small slip foretold a 9.0-magnitude shakedown in that case, or the size of the subsequent tsunami.

Greater warning might have made tremendous difference. It might mean all the difference for us.

Perhaps—just perhaps—we’ll have enough warning to gulp our soup and dash for stable, high ground.

A version of this article appeared in the Victoria Times Colonist.

Canadian Geographic, July 2009

A black Labrador retriever named Tucker is helping researchers determine why orcas summering off southern Vancouver Island are dying.

Tucker lends his nose to science by standing in a moving open-decked motorboat and sniffing the wind to detect orca scat floating on the surface of the Strait of Georgia and Haro Strait. His human colleagues, including Sam Wasser, director of the University of Washington’s Centre for Conservation Biology, scoop of the greenish brown goo and later analyze its hormone levels.

“Killer whale scat doesn’t stay afloat long, and it’s about the same colour as the water,” says Wasser, who uses dogs to study elephants, caribou, spotted owls and other at-risk species. “Without a dog, we’d have a hard time getting enough samples.”

Because Tucker can smell the poop from a long way off, the researchers needn’t crowd the whales. Preliminary analysis of hormones in the scat suggests that boat traffic stresses orcas.

The results from samples collected since 2006 also indicate the whales’ preference for Chinook salmon may be causing them to starve. Stress hormones in the scat peak and thyroid hormones plummet from September through December, when the salmon are at their scarcest. Thyroid hormones help regulate metabolism. When an animal starves, levels drop and metabolism slows. Wasser says the hormone levels mirror observed orca death rates.

“In 2007, thyroid levels in the samples were highest, and no whales died. They were intermediate in 2006, when there was five percent mortality, and lowest in 2008, when mortality decreased to eight percent.”

More samples are needed to confirm the results. Wasser and Tucker will return to the straits to patrol for poop this summer.